How Neobanks Should Monetize Status Signaling

01 Intro

If you’ve been following this blog for a while, you probably know by now that one of my favorite topics to think and write about is “status signaling”.

Signaling explains most of our everyday actions: what clothes we wear, which universities we pick and which religion we subscribe to. Everything has a hidden signaling component with which we communicate our desired tribal affiliation.

In Signaling-as-a-Service, I described the implications signaling has on the monetization of software businesses. For many traditional industries, monetizing the display of status is not a new concept. A Rolex watch, for example, is not better at telling the time than a cheap Casio watch. But a Rolex reveals something about its owners’ wealth and, thus, their status in society. It’s that status message that explains the difference in price.

Similarly, driving a Prius says something about your views on climate change. A Make America Great Again cap reveals something about your political affiliations. And Nike athletic wear signals a healthy, pro-active lifestyle.

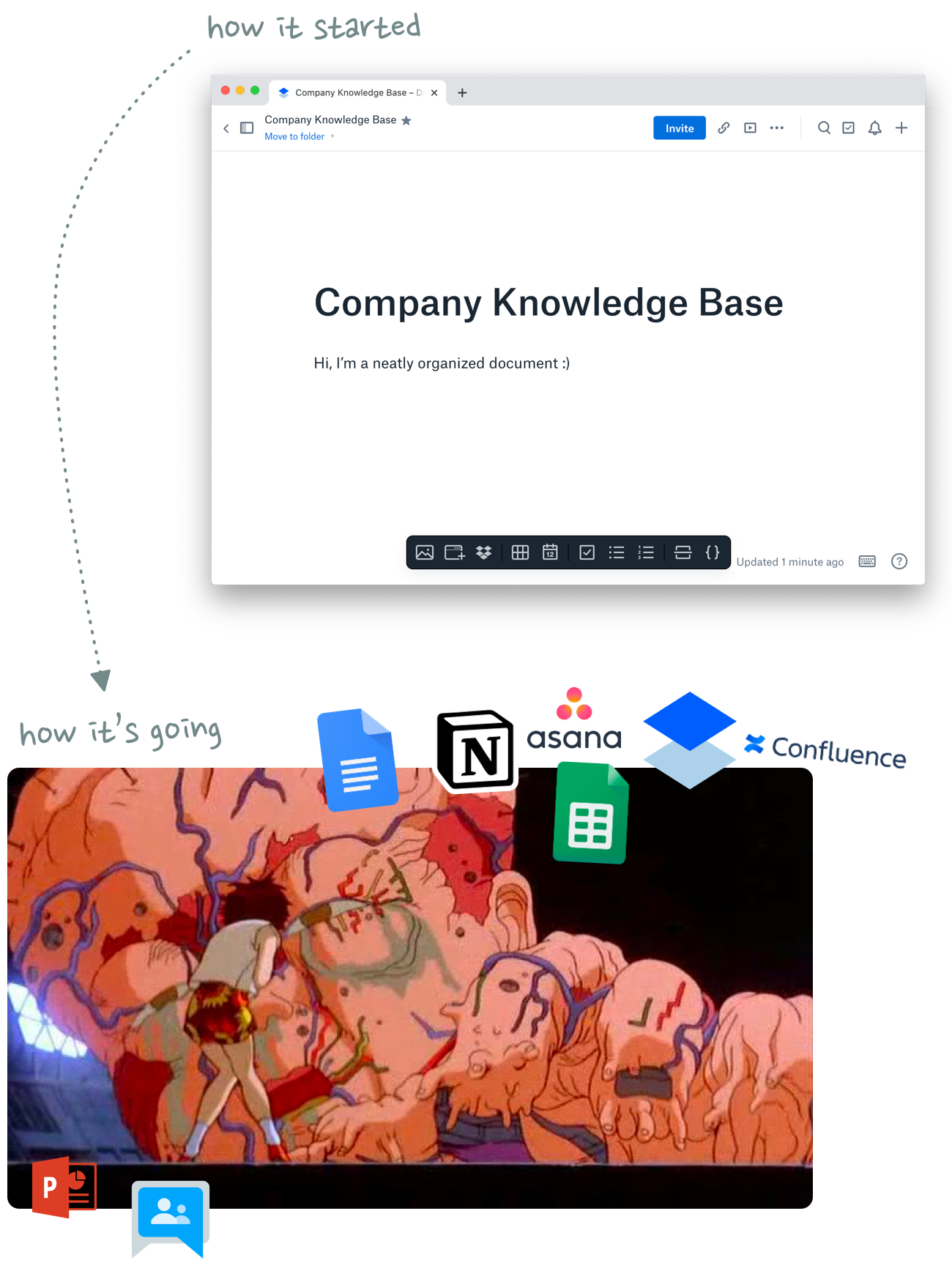

Software is at a crucial disadvantage compared to these physical products because of its intangibility. A fitness app also signals a healthy, pro-active lifestyle, but no one can see it because it only lives on your phone. Everyone can see your Nike gear whenever you wear it in public. Software can’t offer the same benefit. It doesn’t have a signaling distribution channel.

This is why there is no software equivalent of a Rolex watch or a Louis Vuitton handbag. People aren’t willing to spend money on things other people can’t see they spent money on.

But it doesn’t have to be that way. As software is eating the world, the lines between physical and digital products are becoming increasingly blurry. As I have pointed out in my original essay, one way for software companies to solve the signaling distribution problem is to add a physical element to their software product.

In this post I want to explore this idea a little bit further. Specifically, we’ll look at neobanks – and their opportunity to monetize credit card signaling.

02 Neobanks

In the last couple of years we have witnessed the birth and rise of a new startup vertical: neobanks.

Neobanks differ from traditional banks in two ways:

1) Rather than relying on a physical branch network, the entire banking experience is managed via an app

2) Instead of the “how do you do, fellow kids”-cringiness that ad campaigns of traditional banks usually invoke when they try to appeal to a younger audience, neobanks are actually perceived as cool. In fact, many of them feel more like lifestyle brands than banks or tech companies.

Interestingly though, neobanks still use one very traditional banking element: physical cards.

At first glance, this might seem counterintuitive. If you are building a mobile-first bank, why not offer virtual cards and let users pay with their phone? Why go through the hassle of producing and shipping physical cards?

The answer is – you guessed it – signaling.

Think about it: Paying for things (offline) is a social activity. It’s an interaction between at least you and a cashier or waiter. But ideally, in a dinner scenario for example, you are surrounded by other people you want to impress: a date, a group of friends, or work colleagues.

This makes the moment you take out your card to pay the bill a great opportunity to make a statement and build social capital.

If you look at neobanks out there today, it’s pretty obvious that signaling is in fact one of the main benefits they offer – and almost the only thing they monetize (apart from interchange, of course):

- The premium subscriptions neobanks offer usually don’t win on features but solely on nicer looking cards. The N26 or Revolut Metal plans, for example, don’t offer any additional features that really justify the ~€15 / month price tag. They do include a nice looking metal card though – that’s what people pay for.

- Relatedly, it seems like most of the innovation in the industry is happening in card design. The actual banking products are more or less interchangeable, what differs is whether the card comes in titanium, wood, or glow-in-the-dark yellow.

- You may have noticed that the credit card number has moved from the front to the back of the card. This makes it easier for users to share photos of their cards on social media as an additional signaling distribution channel.

Neobanks are popping up like mushrooms after the rain at the moment and it’s unlikely that this trend will end any time soon. Thanks to banking-as-a-service providers, we’ll likely see a lot of non-banking-companies add banking functionalities and cards to their product offering.

There’s an old Twitter joke that every app evolves until it eventually becomes a chat app. The 2020 version of that joke is that every app evolves until it eventually becomes a bank.

When I did some research on credit card designs recently, I was surprised by the sheer amount of different neobanks already in existance. And yet, even though almost all of them offer well-designed cards, it’s shocking how similar they all are. It seems like all of them are focusing on the same target audience instead of differentiating their signaling messages.

Let me explain.

03 In-Groups, Out-Groups and Artificial Scarcity

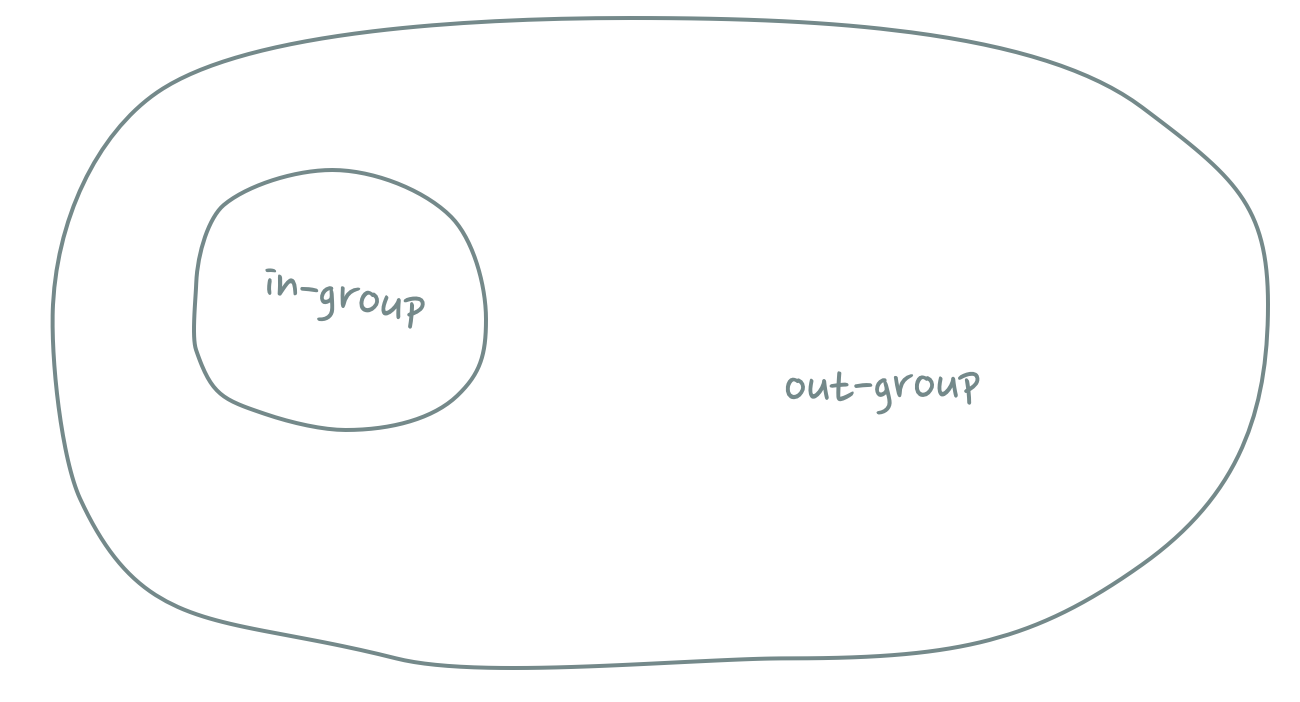

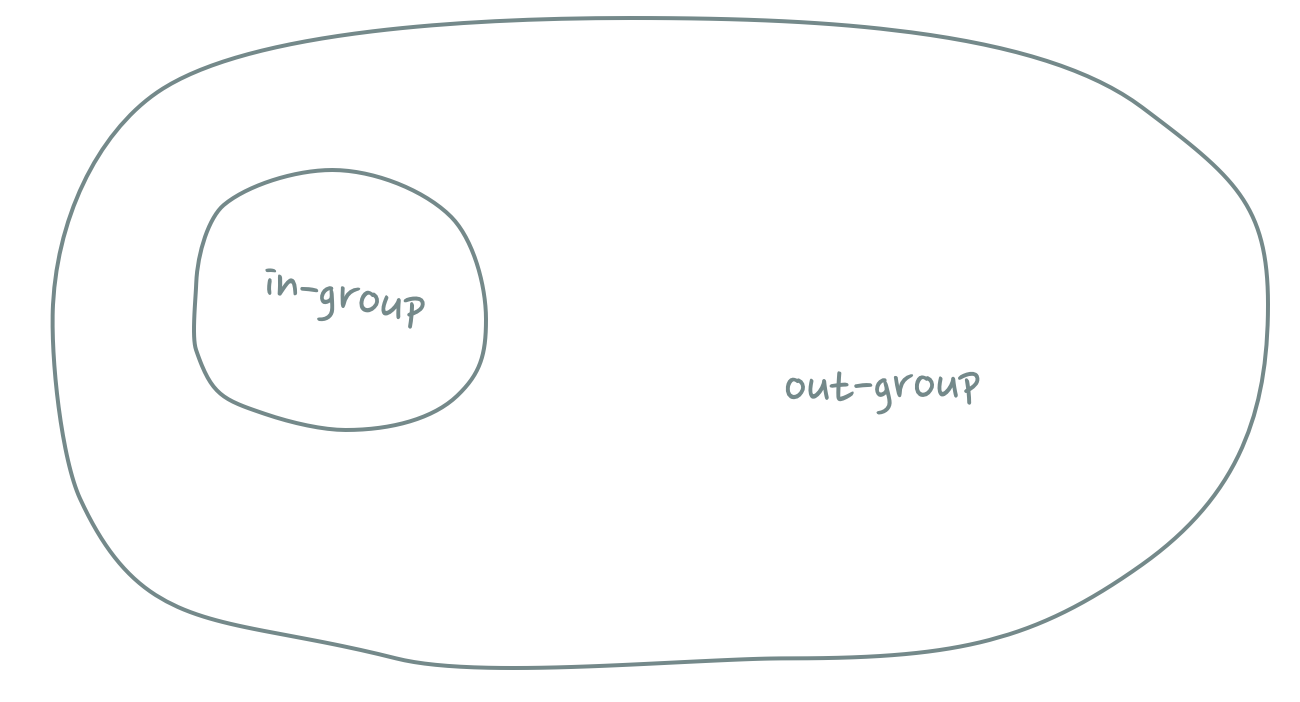

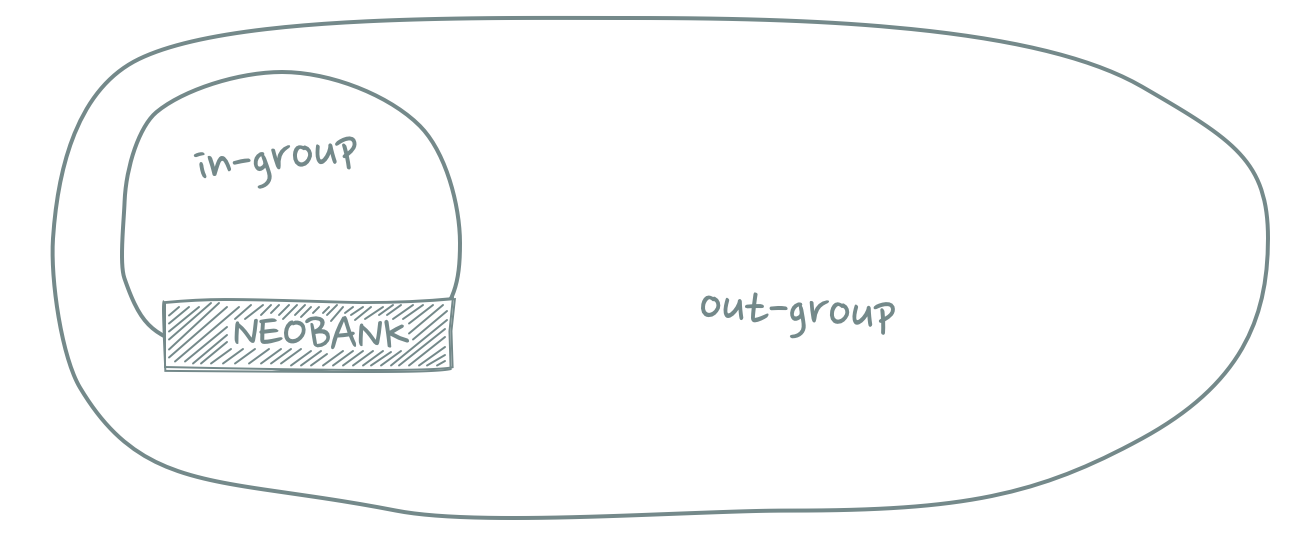

In every signaling scenario there are two possible target audiences: An in-group and an out-group.

The in-group is the tribe you want to join and signal your affiliation to. The out-group is everyone else – people you want to distance yourself from.

iMessage is a great illustration of this: the chat bubble colors clearly indicate who belongs to the in-group (blue = iOS) and who is part of the out-group (green = Android).

It’s important to note that signaling in iMessage is limited to the in-group since these color codes are only visible for iOS users – Android users can’t see who in the group is using which operating system.

Signaling, however, grows stronger the larger the out-group is – as long as the out-group knows about the in-group. This is why luxury car manufacturers deliberately extend their advertising campaigns to people who will never be able to afford their cars: they are increasing the size of the out-group by educating people about the in-group.

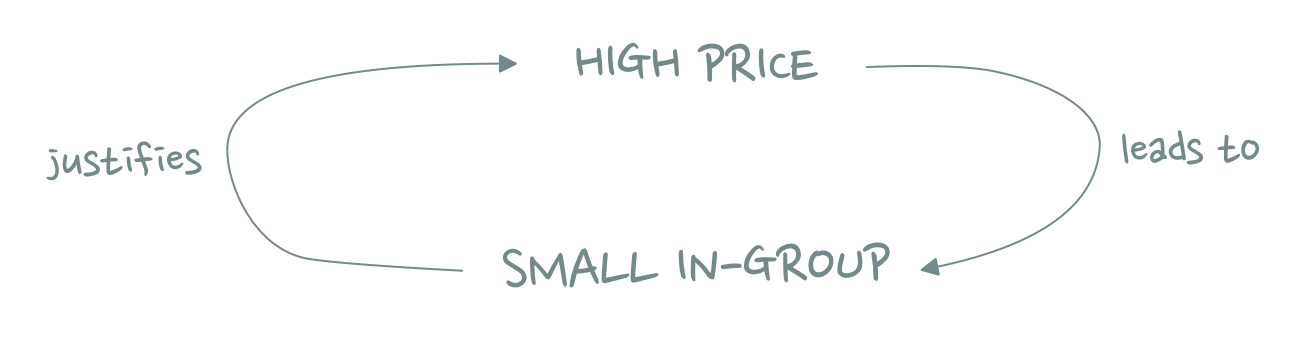

At the same time, brands need to control the size of the in-group. The more exclusive the in-group, the higher the signaling strength and, thus, the monetization potential of a customer.

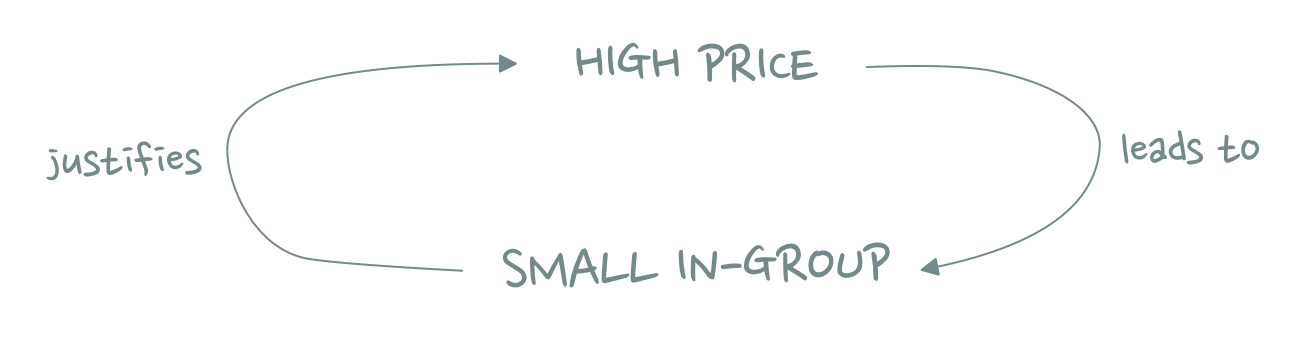

The easiest control mechanism for the size of the in-group is price. If you set the price high enough, few people will be able to afford the product. Ironically, this, in turn, justifies the high price.

Alternatively, companies create artificial scarcity by setting a hard number on supply. Limited supply creates FOMO and hype which increases the size of the out-group and results in higher social status for members of the in-group. Artificial scarcity explains the price of Bitcoin, Pokémon trading cards and why people spend hours queuing in front of Supreme shops.

The problem with keeping the in-group small is that it also limits the number of potential customers and, thus, overall revenue potential. Companies need to walk a fine line between maximizing the number of customers while simultaneously maximizing the number of people they can (afford to) exclude.

04 What Neobanks Should Build

The problem with neobanks today is that they all focus on the same in-group. Here are the premium cards of some of the largest European challenger banks – notice any difference?

It seems like everyone is trying to become the Apple of Banking – including Apple itself. The signaling messages are all about displaying economic power.

But we are slowly seeing new banking apps that are focusing on different audiences. For example, there are now a handful of “green” neobanks that help users signal environmental altruism.

Or how about this Razer Card targeted at the gamer community?

The question for these companies and their investors is whether the in-group is big enough to justify building an entire bank around it. Making the unit economics of a bank work requires a certain amount of users, but as we discussed earlier, the signaling strength decreases as the size of in-group increases.

So how do you solve this problem?

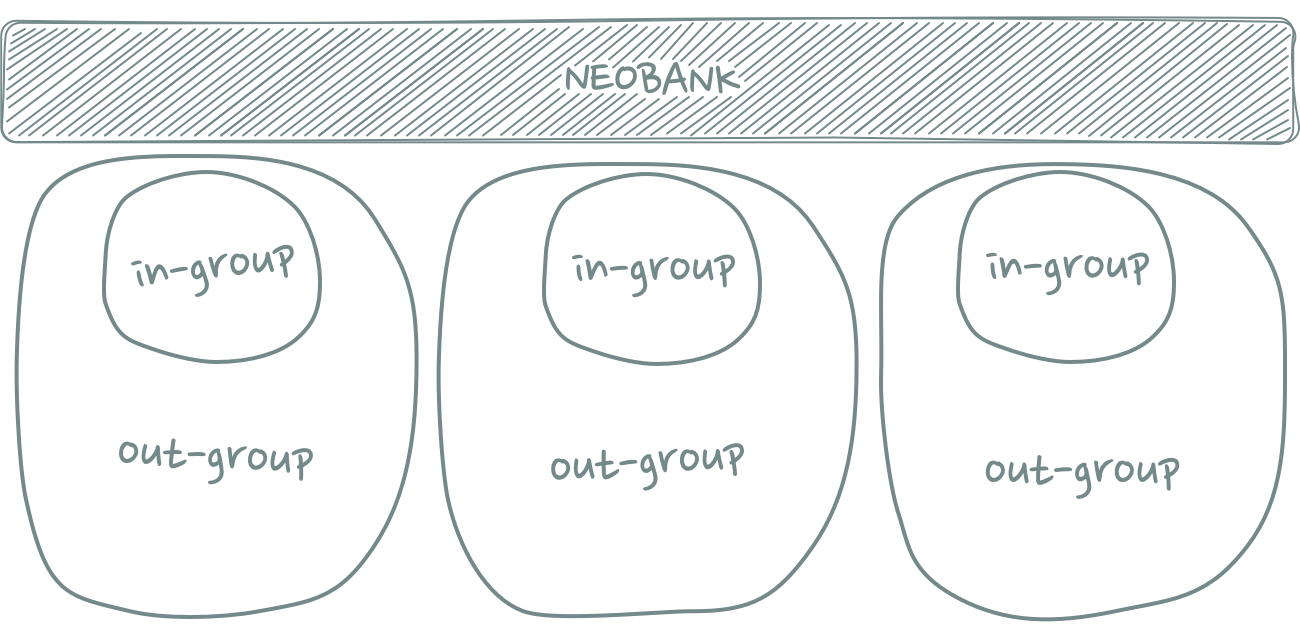

By introducing multiple in-groups.

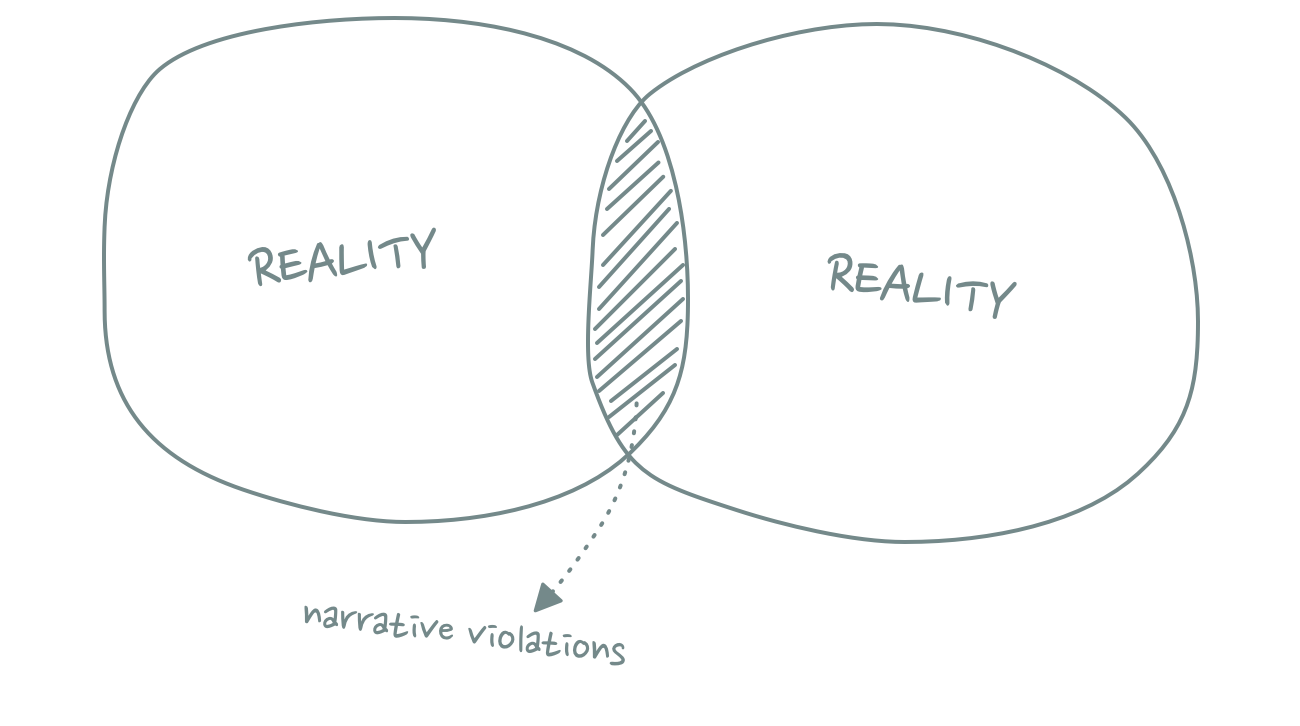

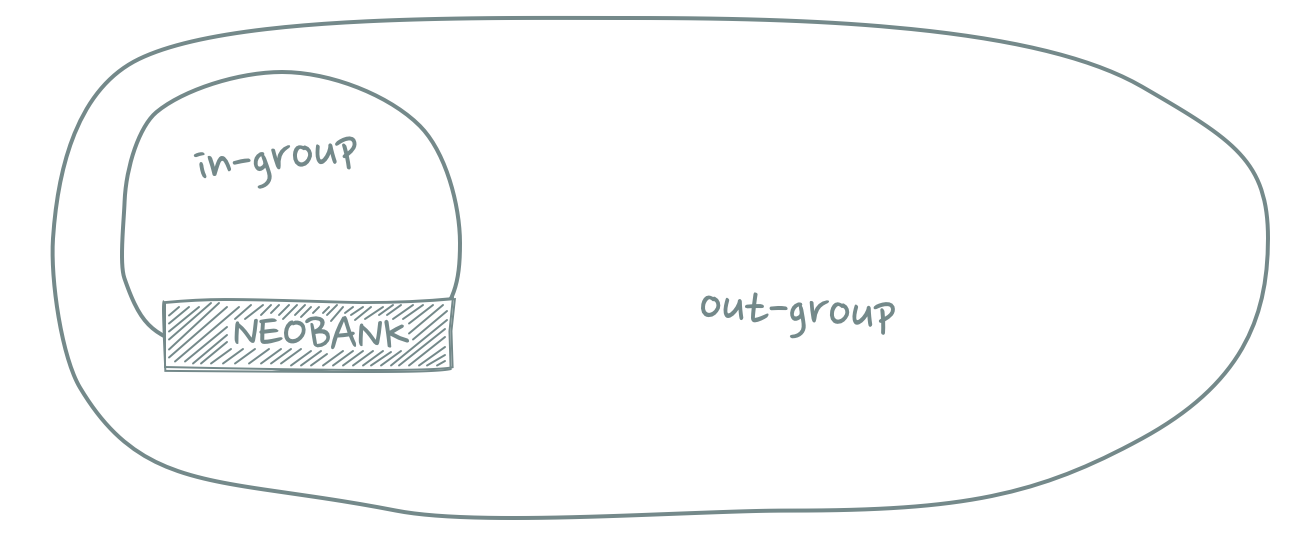

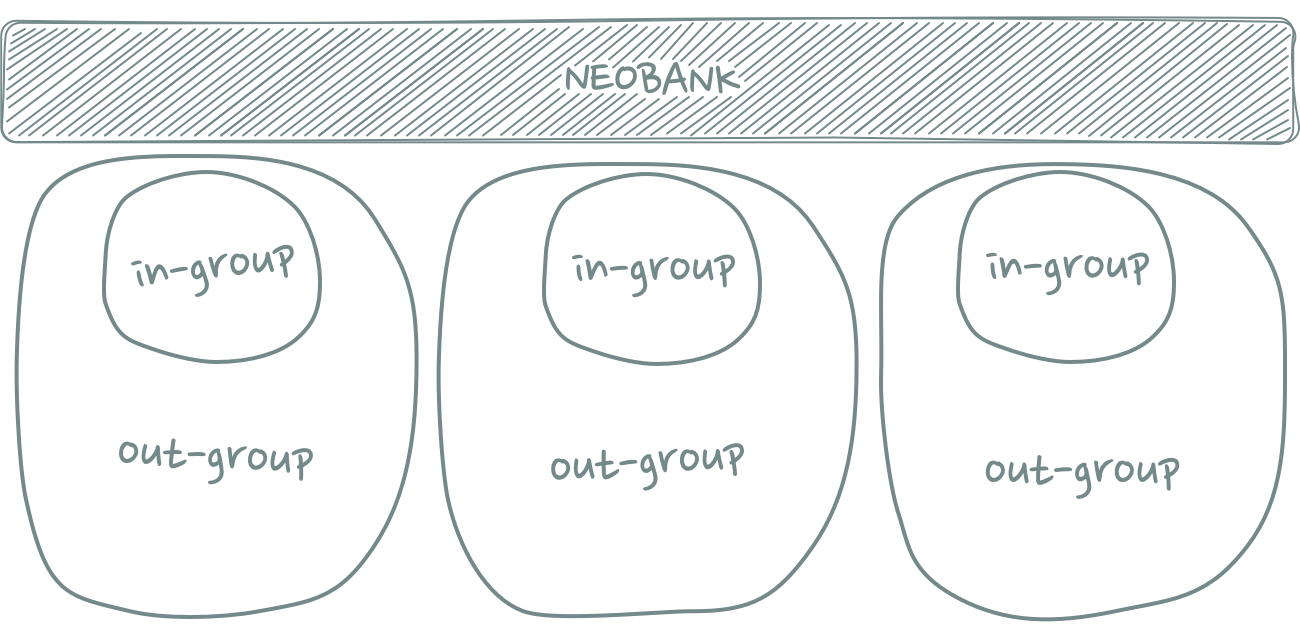

See, the current model looks like this:

(In fact, given how undifferentiated most of the offerings and cards are, there are actually multiple neobanks within the same small in-group bubble.)

But what if one bank would target multiple, different in-groups?

For example, what if N26 had dedicated cards for soccer fans, hip-hop enthusiasts and gamers? Instead of focusing on just one signaling audience, their total addressable market would massively increase.

The way they would target these audiences is via brand collaborations. N26 does not have the necessary reputation in any of the above-mentioned areas to build credible signaling messages. It would not be able to build attractive in-groups on its own – but other brands could lend N26 their social capital.

Apple has long worked with RED, IKEA recently teamed up with Virgil Abloh, and Nike partners with Headspace. Why wouldn’t this concept work for neobanks?

What would N26 x Manchester United look like?

Or Chime x Supreme?

Or Revolut x 100 Thieves?

Because of a bigger target audience overall, individual in-groups could be kept smaller. Cards could be released as limited edition drops transforming them into collectibles, which would justify a higher price tag per card.

It’s worth noting that different signaling audiences are not mutually exclusive. We don’t just subscribe to a single in-group – our identities are prismatic. This means that some users might purchase multiple cards to signal to different in- and out-groups resulting in even higher expected LTV per user.

A few neobanks have already started to experiment with brand collaborations and limited edition cards (see Cash App x Hood By Air or Point x Laura Berger). I expect there will be a lot more once neobanks realize what most of them really are: Signaling-as-a-Service companies.

05 A Closing Ask

What card designs and neobank collaborations would you like to see? Let me know in this Twitter thread – I’d love to hear your ideas!

And if you’re an (aspiring) 3D artist or designer: Would you like to bring some of these card ideas to life? There will be a follow-up post to this essay featuring the best card mock-ups. Send me a Twitter DM or email (hello at julianlehr dot com) if you want to learn more.

Thanks to Brandon Jacoby, Jan König, Mario Gabriele, Max Cutler and Zack Hargett for reading drafts of this post.

What Harari doesn’t discuss in his book is the extreme other end of this cognitive ability: Conspiracy theories. I’ve been fascinated by

What Harari doesn’t discuss in his book is the extreme other end of this cognitive ability: Conspiracy theories. I’ve been fascinated by