(Thoughts on Ecommerce, Pt 1)

With much fanfare and many hot takes on Twitter, Shopify launched one of their “most significant products ever” a few days ago: a consumer-facing shopping app, simply called Shop.

Many have been interpreting this as a massive shift in Shopify’s strategy to compete more directly with Amazon.

I’m not so sure that’s the case.

Inspired by the launch of Shop, I decided to write a two-part essay on ecommerce. The first part – the article you’re reading right now – looks at the current state of online shopping. It explains the business model behind Shopify (and Amazon) and how Shop fits into that strategy.

The second part – which I’ll release next week – is an outlook on the future of ecommerce. It describes what I believe is currently missing in the shopping experience and what Shopify should build next.

Let’s dive into it.

To start things off, let’s first take a look at how Shopify and Amazon operate – because while both of them are ecommerce companies, their strategies are actually fundamentally different.

(Disclaimer: This section is essentially a brash copy summary of Ben Thompson’s excellent analysis on the same topic)

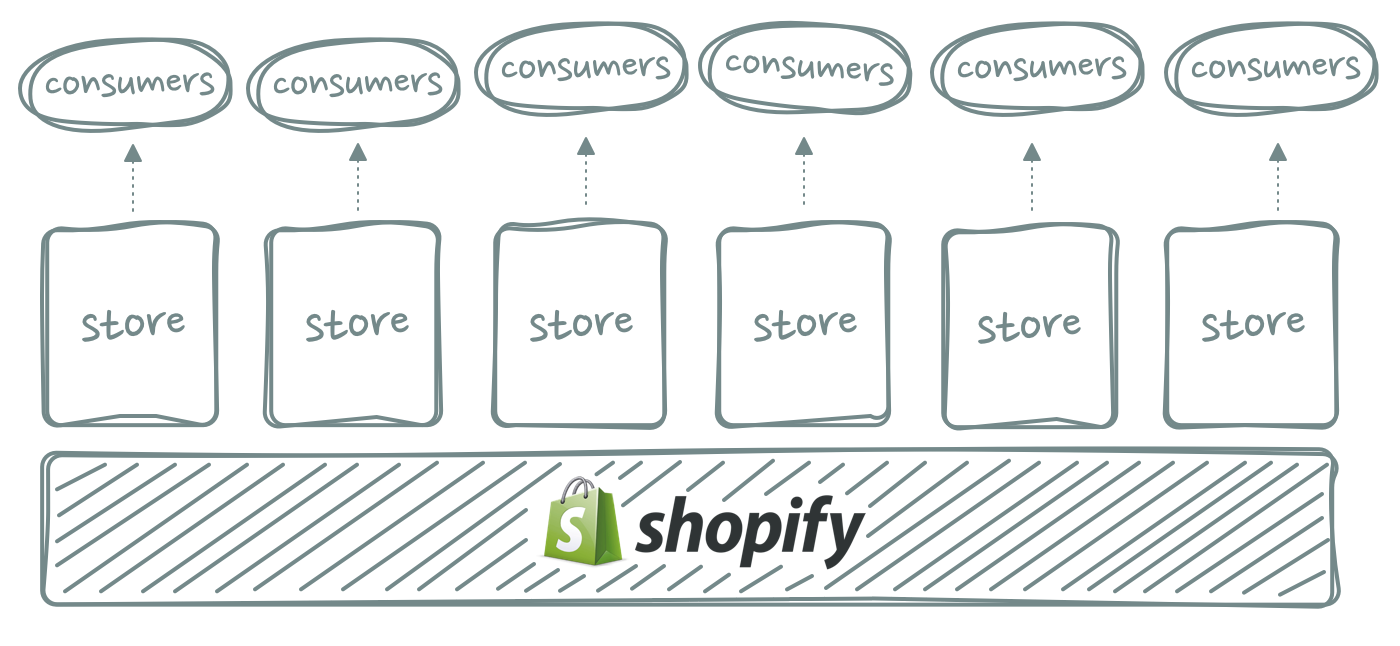

Shopify is first and foremost an infrastructure company. It provides a platform on which merchants can build their own stores to have a direct relationship with their end customers. This is why the type of business Shopify enables is often referred to as “direct to consumer” (D2C).

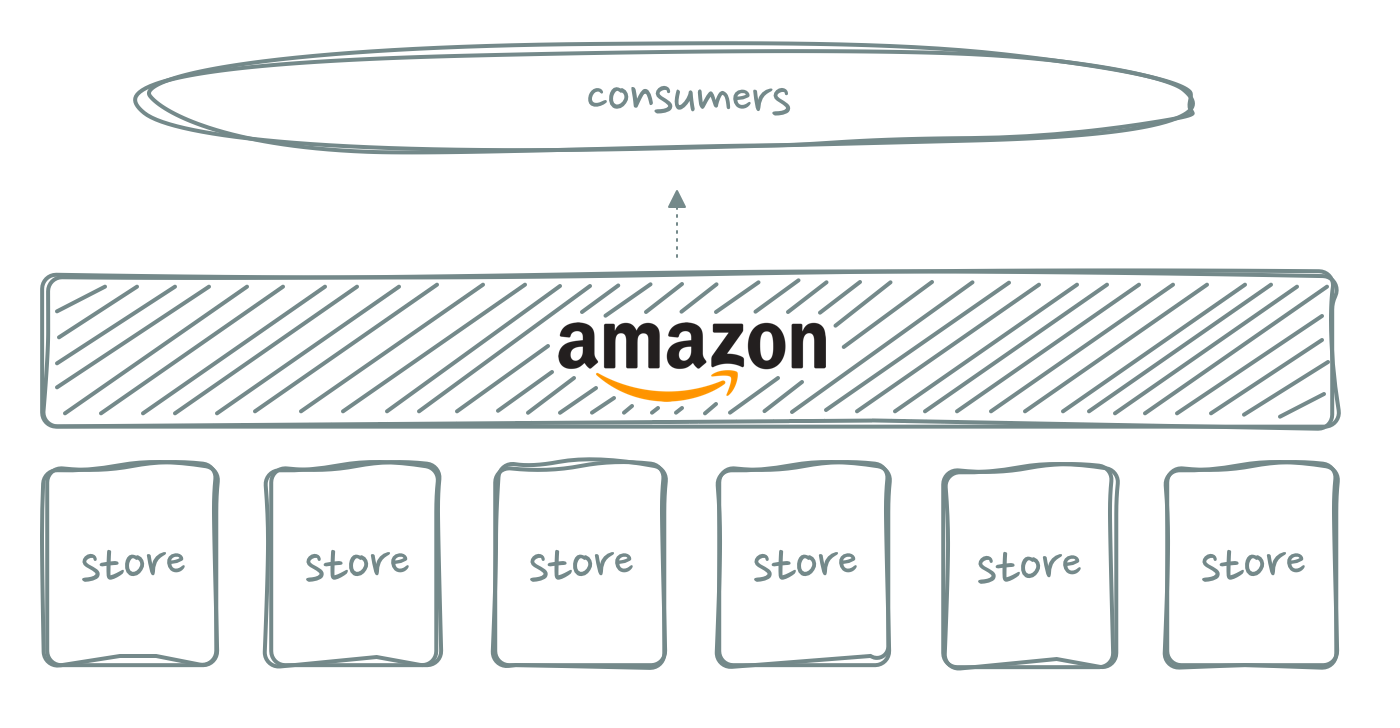

Amazon, on the other hand, is more of an aggregator. Alongside its own supply, Amazon lets any merchant sell their products on the Amazon.com website. But it is always Amazon which owns the customer relationship – never the merchant. The supply side becomes commoditized.

It’s not just the two companies’ strategies that are different – they also serve two completely different types of shopping behavior.

Any internet service can broadly be categorized based on two types of user actions: Pull and push.

Google is the perfect example of a Pull service. Users are actively looking for a particular piece of information or an answer to a specific question (e.g. “how to make pancakes?” or “are koalas bears?“). Google’s search engine lets you pull that information.

Facebook, on the other hand, is a typical Push service. The user behavior is a lot more passive since you don’t have to actively ask for information. Instead, Facebook automatically pushes the most relevant content into your newsfeed.

Amazon is essentially the Google of ecommerce. It’s primarily a search engine and works best when you already have an idea of what you want to buy. Amazon is not great at discovery though. It doesn’t show you things you didn’t even know you were interested in.

So who, then, is the Facebook of ecommerce?

That question is a little more difficult because there’s not one clear answer. Instead of one dedicated platform for product discovery, we have seen social networks like Instagram and Pinterest slowly morph into product discovery channels. And the fact that they are not pure ecommerce apps, but insert products between organic content, is probably exactly why they perform so well.

The types of products that work particularly well on Instagram are things that are visually appealing. You don’t see ads for HDMI cables or windshield phone mounts on Instagram – those are typical Amazon products.

Instead, it’s products like jewelry, cosmetics, fashion or home accessories that do well on Instagram – and those are classic Shopify D2C brands.

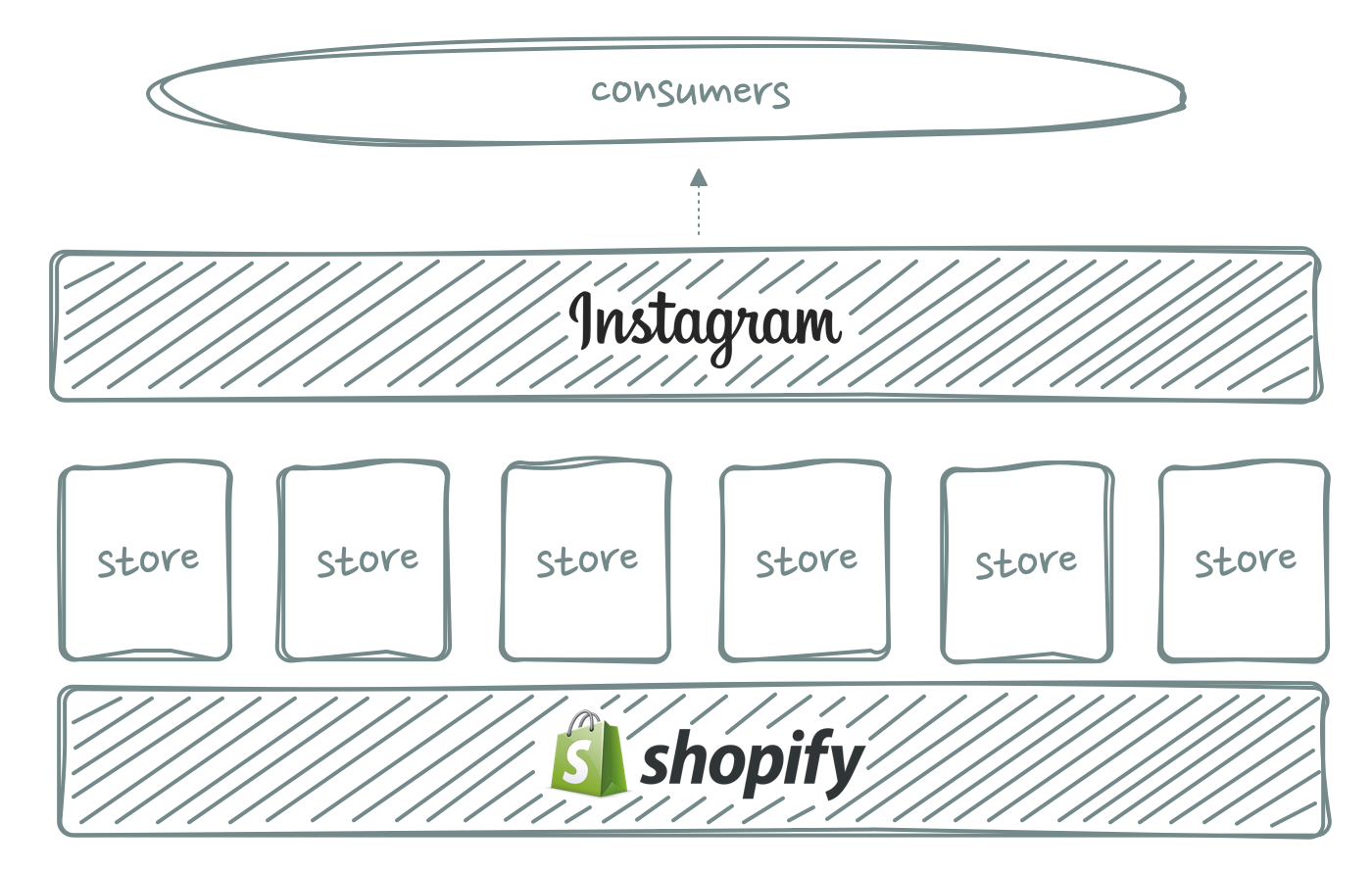

Shopify is powering the infrastructure of the “Facebook for ecommerce”, but it doesn’t own or control the entire channel. And that’s a risk.

Shopify’s model actually looks a bit more like this:

While some of that Instagram traffic might be organic, the most significant chunk of customers is coming from auction-based ads (due to Instagram’s no-link-policy). This means that as competition increases (and it always does once one D2C brand in a particular segment sees some success, because there aren’t any real barriers to entry), ad prices go up.

As a result, many of Shopify’s merchants aren’t really direct-to-consumer brands, they are more like direct-to-consumer-but-with-Instagram-in-the-middle-eating-all-of-their-margin brands.

Instagram capturing most of the value is a perfect example of why demand aggregation is always more powerful than supply aggregation. Too much reliance on a powerful gatekeeper like Instagram is a risk for Shopify and its merchants.

Luckily for Shopify though, there are several ways to mitigate that risk.

The first thing to note is that Instagram isn’t the only product discovery channel driving traffic to Shopify stores. As mentioned earlier, there is not one leading contestant for the role of “Facebook for Ecommerce”. Pinterest, YouTube and Twitter are also product discovery engines (among many other services trying to do the same).

One of Shopify’s options is therefore to diversify the portfolio of user acquisition channels its merchants can use. This is why I find Shopify’s Pinterest and Google Shopping partnership announcements from the last few weeks way more interesting than the launch of Shop.

Shop has been touted as Shopify’s own product discovery channel – which would be another way to tackle its current dependence on other platforms. Instead of relying on Instagram traffic, Shopify could simply start aggregating the demand side itself and become more of a marketplace like Amazon.

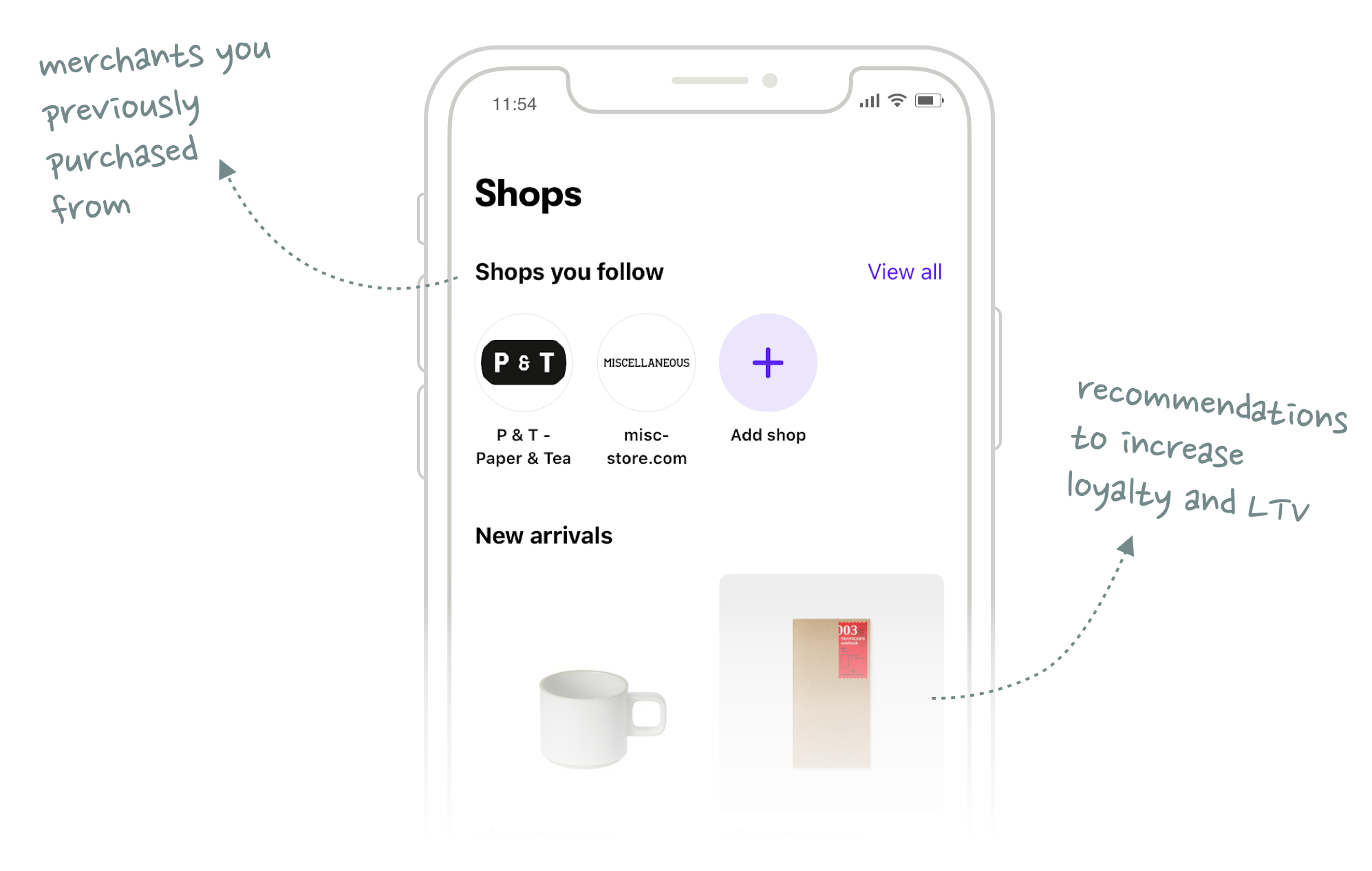

But if you install and open Shop, you’ll notice that that’s not really what the app does. Instead of a feed with product recommendations, Shop connects you with merchants you have purchased from in the past.

Here is why:

Another option to defend Shopify merchants against ever increasing customer acquisition costs (read Instagram ads) is to simultaneously increase customer lifetime value. This is exactly what Shop is supposed to do.

By connecting you with merchants you have bought from before, Shop will recommend you additional products that you might be interested in from the same sellers. The result is higher post-purchase loyalty and thus higher LTV which makes it easier to justify high initial acquisition costs via Instagram.

That being said, it’s not difficult to imagine a future where Shopify also starts recommending products from other merchants. What exactly this should look like is the topic of part two of this essay, which you can read here.

Do you have feedback or thoughts on this post?

If so, I’d love to hear them!

Thanks to Jan König for reading drafts of this post.