Conversational interfaces are a bit of a meme. Every couple of years a shiny new AI development emerges and people in tech go “This is it! The next computing paradigm is here! We’ll only use natural language going forward!”. But then nothing actually changes and we continue using computers the way we always have, until the debate resurfaces a few years later.

We’ve gone through this cycle a couple of times now: Virtual assistants (Siri), smart speakers (Alexa, Google Home), chatbots (“conversational commerce”), AirPods-as-a-platform, and, most recently, large language models.

I’m not entirely sure where this obsession with conversational interfaces comes from. Perhaps it’s a type of anemoia, a nostalgia for a future we saw in StarTrek that never became reality. Or maybe it’s simply that people look at the term “natural language” and think “well, if it’s natural then it must be the logical end state”.

I’m here to tell you that it’s not.

When people say “natural language” what they mean is written or verbal communication. Natural language is a way to exchange ideas and knowledge between humans. In other words, it’s a data transfer mechanism.

Data transfer mechanisms have two critical factors: speed and lossiness.

Speed determines how quickly data is transferred from the sender to the receiver, while lossiness refers to how accurately the data is transferred. In an ideal state, you want data transfer to happen at maximum speed (instant) and with perfect fidelity (lossless), but these two attributes are often a bit of a trade-off.

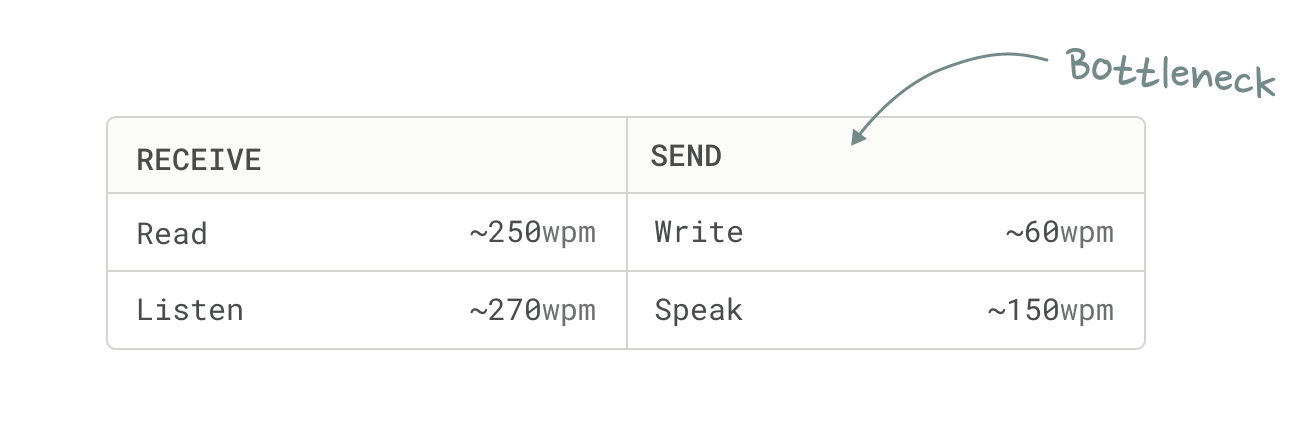

Let’s look at how well natural language does on the speed dimension:

The first thing I should note is that these data points are very, very simplified averages. The important part to take away from this table is not the accuracy of individual numbers, but the overall pattern: We are significantly faster at receiving data (reading, listening) than sending it (writing, speaking). This is why we can listen to podcasts at 2x speed, but not record them at 2x speed.

To put the writing and speaking speeds into perspective, we form thoughts at 1,000-3,000 words per minute. Natural language might be natural, but it’s a bottleneck.

And yet, if you think about your day-to-day interactions with other humans, most communication feels really fast and efficient. That’s because natural language is only one of many data transfer mechanisms available to us.

For example, instead of saying “I think what you just said is a great idea”, I can just give you a thumbs up. Or nod my head. Or simply smile.

Gestures and facial expressions are effectively data compression techniques. They encode information in a more compact, but lossier, form to make it faster and more convenient to transmit.

Natural language is great for data transfer that requires high fidelity (or as a data storage mechanism for async communication), but whenever possible we switch to other modes of communication that are faster and more effortless. Speed and convenience always wins.

My favorite example of truly effortless communication is a memory I have of my grandparents. At the breakfast table, my grandmother never had to ask for the butter – my grandfather always seemed to pass it to her automatically, because after 50+ years of marriage he just sensed that she was about to ask for it. It was like they were communicating telepathically.

*That* is the type of relationship I want to have with my computer!

Similar to human-to-human communication, there are different data transfer mechanisms to exchange information between humans and computers. In the early days of computing, users interacted with computers through a command line. These text-based commands were effectively a natural language interface, but required precise syntax and a deep understanding of the system.

The introduction of the GUI primarily solved a discovery problem: Instead of having to memorize exact text commands, you could now navigate and perform tasks through visual elements like menus and buttons. This didn’t just make things easier to discover, but also more convenient: It’s faster to click a button than to type a long text command.

Today, we live in a productivity equilibrium that combines graphical interfaces with keyboard-based commands.

We still use our mouse to navigate and tell our computers what to do next, but routine actions are typically communicated in form of quick-fire keyboard presses: ⌘b to format text as bold, ⌘t to open a new tab, ⌘c/v to quickly copy things from one place to another, etc.

These shortcuts are not natural language though. They are another form of data compression. Like a thumbs up or a nod, they help us to communicate faster.

Modern productivity tools take these data compression shortcuts to the next level. In tools like Linear, Raycast or Superhuman every single command is just a keystroke away. Once you’ve built the muscle memory, the data input feels completely effortless. It’s almost like being handed the butter at the breakfast table without having to ask for it.

Touch-based interfaces are considered the third pivotal milestone in the evolution of human computer interaction, but they have always been more of an augmentation of desktop computing rather than a replacement for it. Smartphones are great for “away from keyboard” workflows, but important productivity work still happens on desktop.

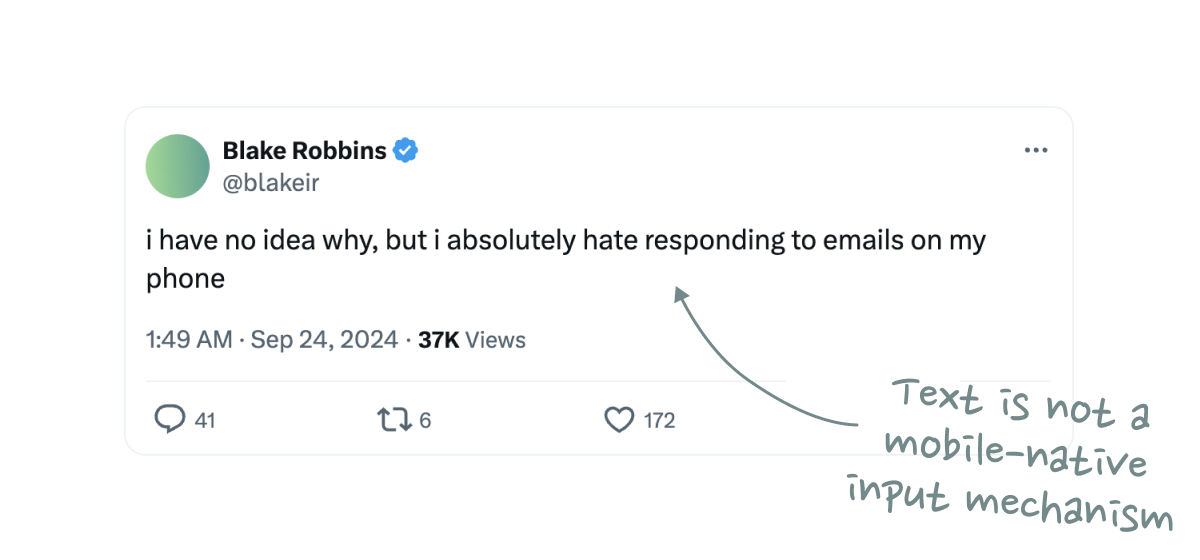

That’s because text is not a mobile-native input mechanism. A physical keyboard can feel like a natural extension of your mind and body, but typing on a phone is always a little awkward – and it shows in data transfer speeds: Average typing speeds on mobile are just 36 words-per-minute, notably slower than the ~60 words-per-minute on desktop.

We’ve been able to replace natural language with mobile-specific data compression algorithms like emojis or Snapchat selfies, but we’ve never found a mobile equivalent for keyboard shortcuts. Guess why we still don’t have a truly mobile-first productivity app after almost 20 years since the introduction of the iPhone?

“But what about speech-to-text,” you might say, pointing to reports about increasing usage of voice messaging. It’s true that speaking (150wpm) is indeed a faster data transfer mechanism than typing (60wpm), but that doesn’t automatically make it a better method to interact with computers.

We keep telling ourselves that previous voice interfaces like Alexa or Siri didn’t succeed because the underlying AI wasn’t smart enough, but that’s only half of the story. The core problem was never the quality of the output function, but the inconvenience of the input function: A natural language prompt like “Hey Google, what’s the weather in San Francisco today?” just takes 10x longer than simply tapping the weather app on your homescreen.

LLMs don’t solve this problem. The quality of their output is improving at an astonishing rate, but the input modality is a step backwards from what we already have. Why should I have to describe my desired action using natural language, when I could simply press a button or keyboard shortcut? Just pass me the goddamn butter.

None of this is to say that LLMs aren’t great. I love LLMs. I use them all the time. In fact, I wrote this very essay with the help of an LLM.

Instead of drafting a first version with pen and paper (my preferred writing tools), I spent an entire hour walking outside, talking to ChatGPT in Advanced Voice Mode. We went through all the fuzzy ideas in my head, clarified and organized them, explored some additional talking points, and eventually pulled everything together into a first outline.

This wasn’t just a one-sided “Hey, can you write a few paragraphs about x” prompt. It felt like a genuine, in-depth conversation and exchange of ideas with a true thought partner. Even weeks later, I’m still amazed at how well it worked. It was one of those rare, magical moments where software makes you feel like you’re living in the future.

In contrast to typical human-to-computer commands, however, this workflow is not defined by speed. Like writing, my ChatGPT conversation is a thinking process – not an interaction that happens post-thought.

It should also be noted that ChatGPT does not substitute any existing software workflows in this example. It’s a completely new use case.

This brings me to my core thesis: The inconvenience and inferior data transfer speeds of conversational interfaces make them an unlikely replacement for existing computing paradigms – but what if they complement them?

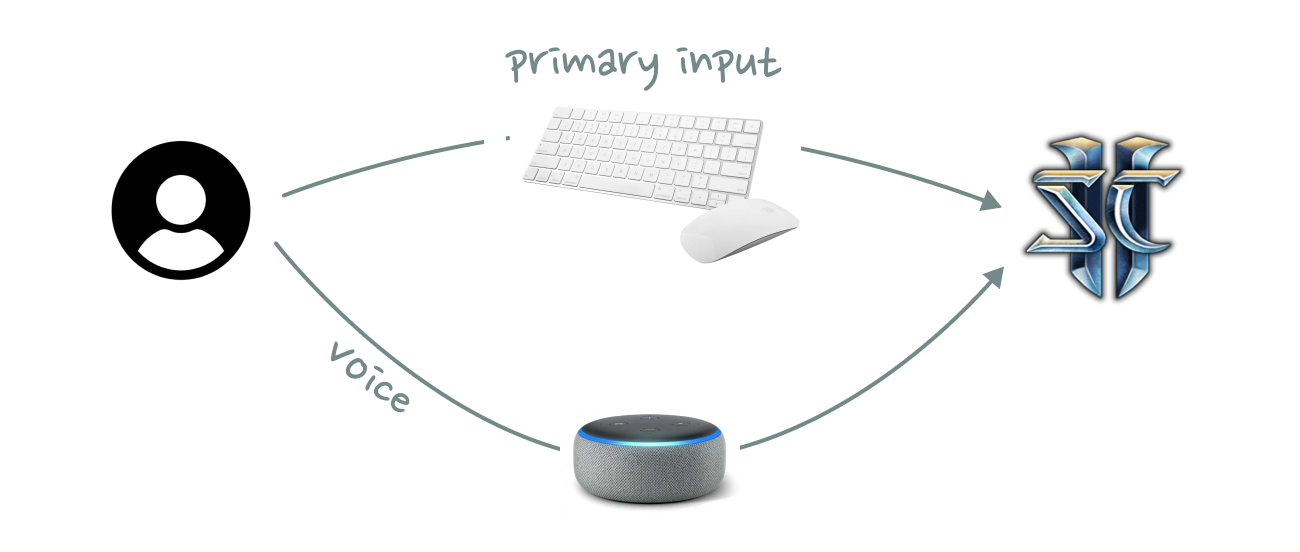

The most convincing conversational UI I have seen to date was at a hackathon where a team turned Amazon Alexa into an in-game voice assistant for StarCraft II. Rather than replacing mouse and keyboard, voice acted as an additional input mechanism. It increased the bandwidth of the data transfer.

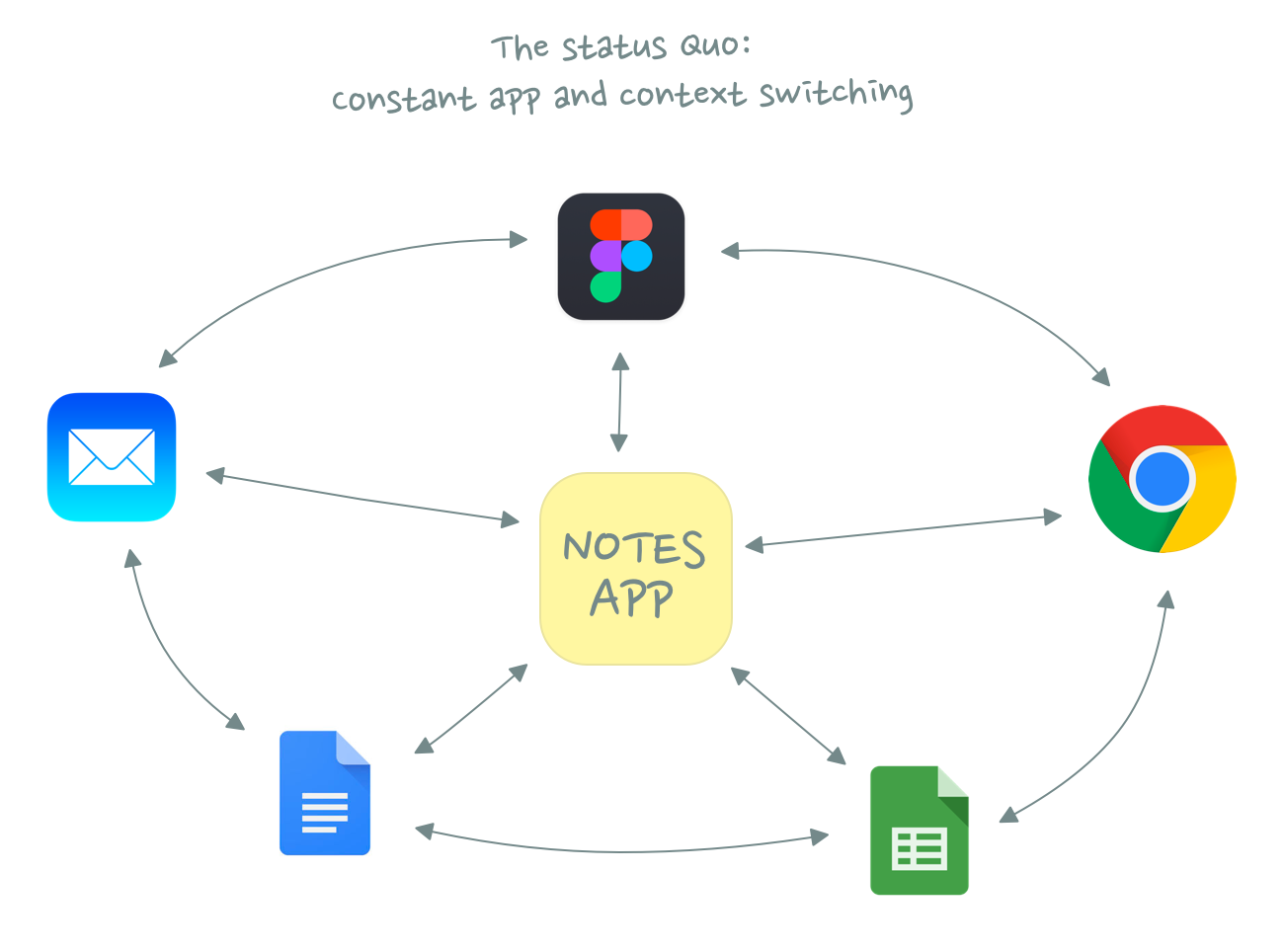

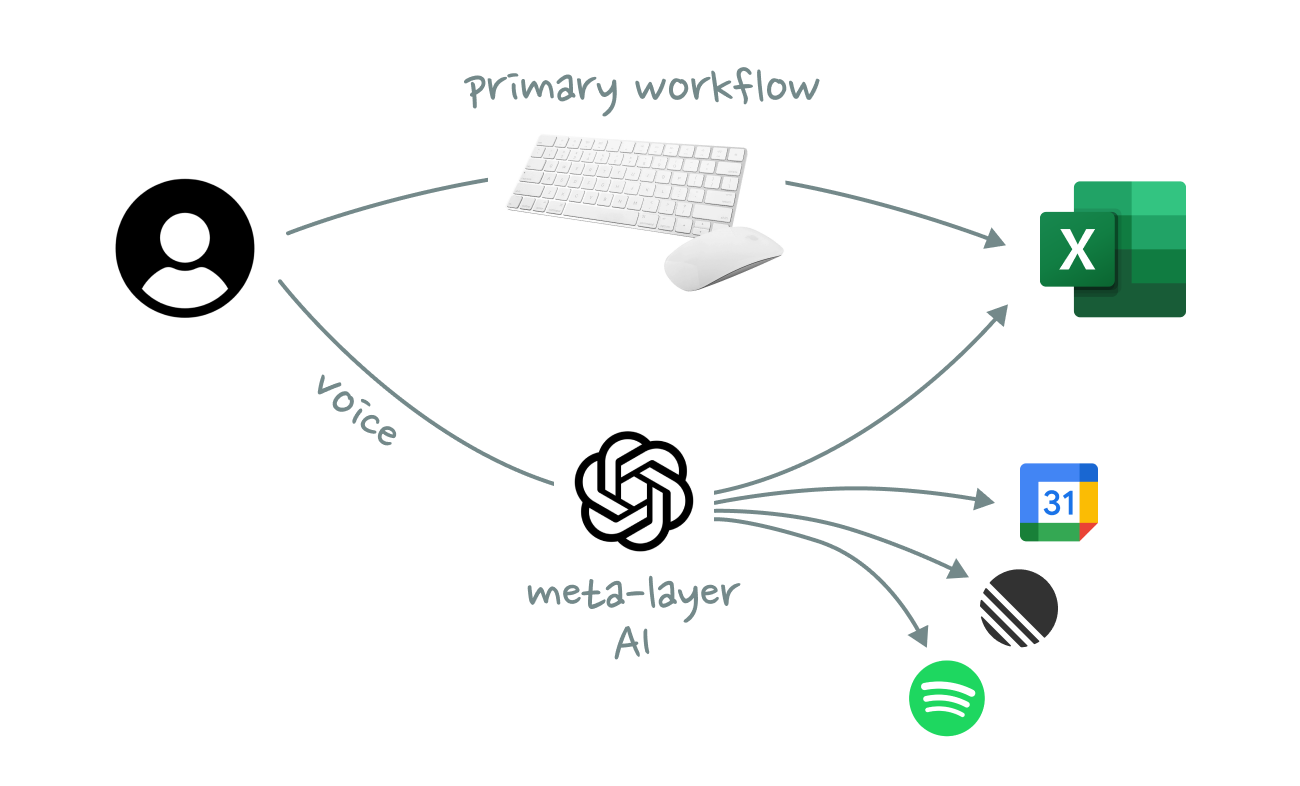

You could see the same pattern work for any type of knowledge work, where voice commands are available while you are busy doing other things. We will not replace Figma, Notion, or Excel with a chat interface. It’s not going to happen. Neither will we forever continue the status quo, where we constantly have to switch back and forth between these tools and an LLM.

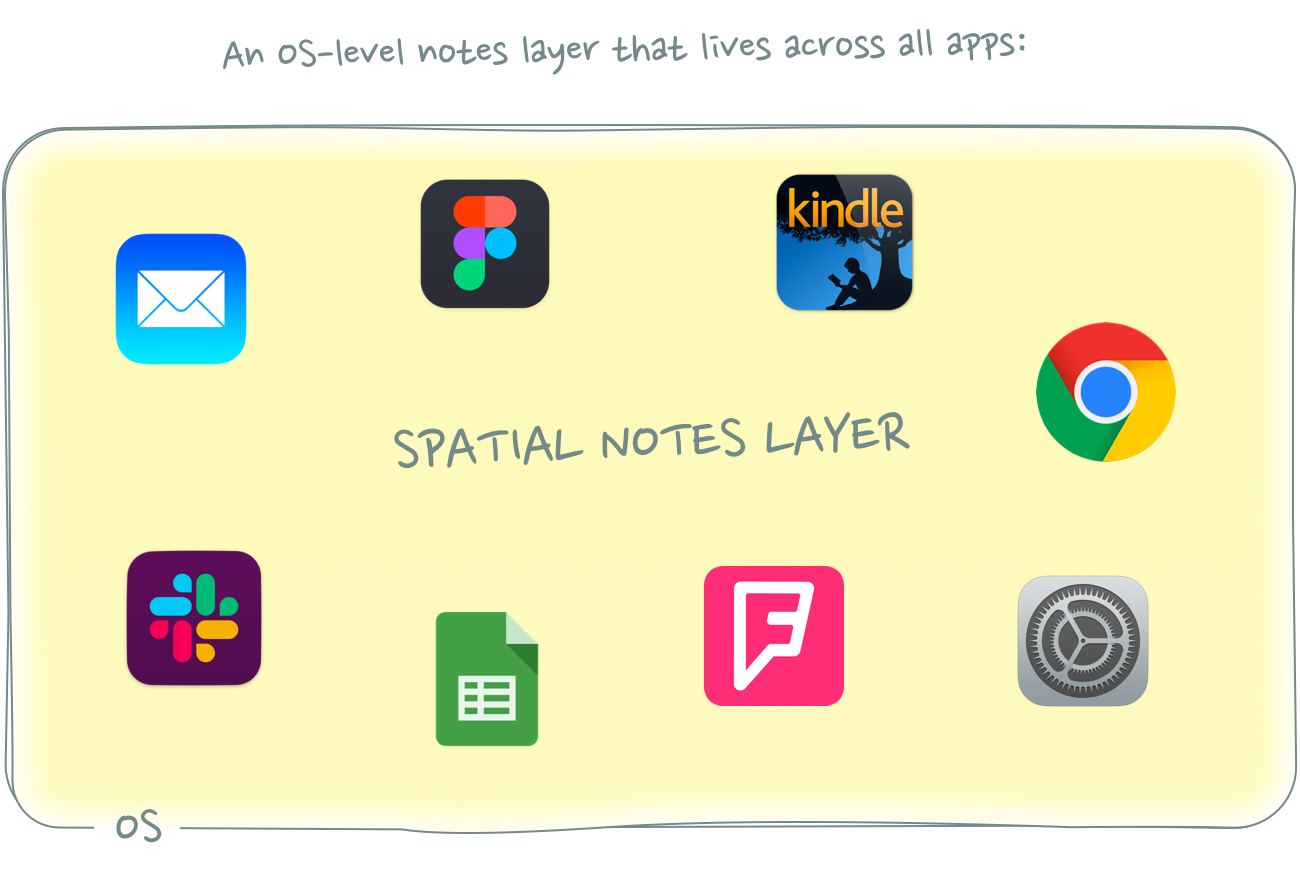

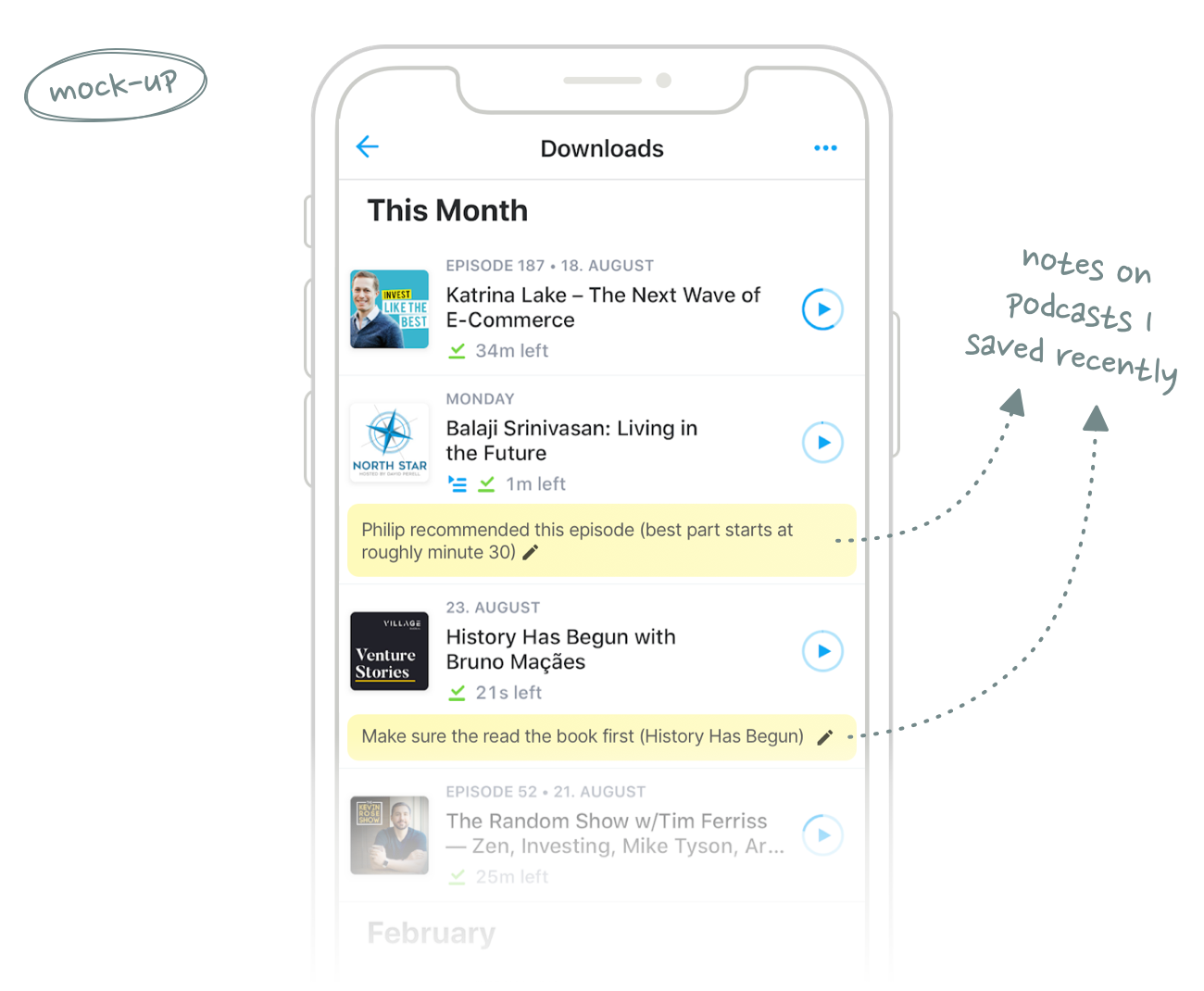

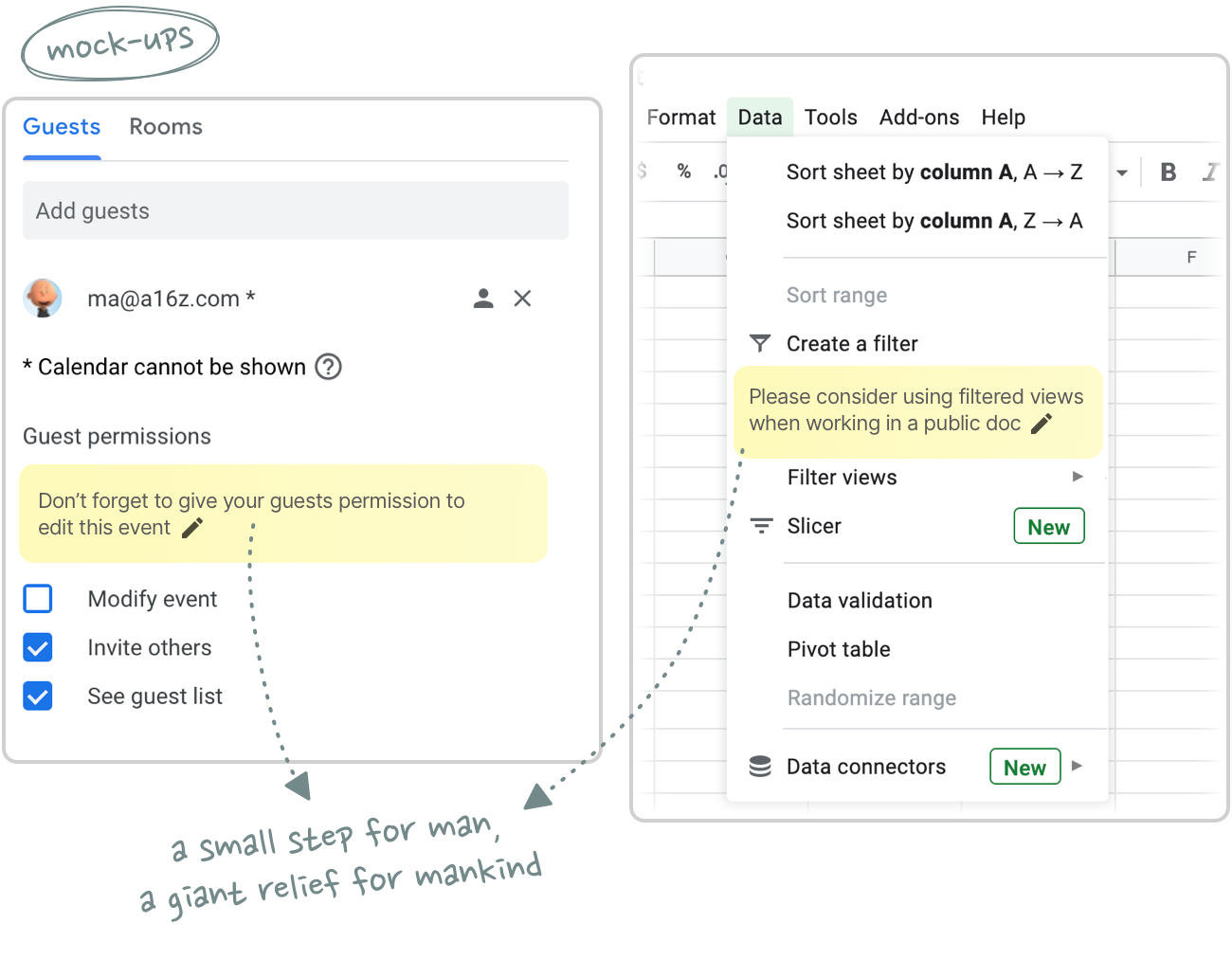

Instead, AI should function as an always-on command meta-layer that spans across all tools. Users should be able to trigger actions from anywhere with simple voice prompts without having to interrupt whatever they are currently doing with mouse and keyboard.

For this future to become an actual reality, AI needs to work at the OS level. It’s not meant to be an interface for a single tool, but an interface across tools. Kevin Kwok famously wrote that “productivity and collaboration shouldn’t be two separate workflows”. And while he was referring to human-to-human collaboration, the statement is even more true in a world of human-to-AI collaboration, where the lines between productivity and coordination are becoming increasingly more blurry.

The second thing we need to figure out is how we can compress voice input to make it faster to transmit. What’s the voice equivalent of a thumbs-up or a keyboard shortcut? Can I prompt Claude faster with simple sounds and whistles? Should ChatGPT have access to my camera so it can change its answers in realtime based on my facial expressions?

Even as a secondary interface, speed and convenience is all that matters.

I admit that the title of this essay is a bit misleading (made you click though, didn’t it?). This isn’t really a case against conversational interfaces, it’s a case against zero-sum thinking.

We spend too much time thinking about AI as a substitute (for interfaces, workflows, and jobs) and too little time about AI as a complement. Progress rarely follows a simple path of replacement. It unlocks new, previously unimaginable things rather than merely displacing what came before.

The same is true here. The future isn’t about replacing existing computing paradigms with chat interfaces, but about enhancing them to make human-computer interaction feel effortless – like the silent exchange of butter at a well-worn breakfast table.

Thanks to Blake Robbins, Chris Paik, Jackson Dahl, Johannes Schickling, Jordan Singer, and signüll for reading drafts of this post.